ARTIST CONVO: CHLOE COLLYER

DISCUSSING TEACHING, SURVEILLANCE, AND THEIR RECENT MULTIMEDIA PROJECT “BOILING POINT”

INTERVIEW BY MERON MENGHISTAB

“Chloe Collyer has been documenting Seattle for as long as I can remember” was the first thing I said to photojournalist Chloe Collyer as we got comfortable at Caffe Vita in Seward Park.

If you keep up with Seattle publications, you’ve seen Chloe’s coverage of protests, events, community gatherings, and museum functions over the years. Now their protest coverage has culminated into a mixed-media project, “Boiling Point” which synthesizes a decade of Seattle-area protests. With this work, they have taken years of digital photography and combined it with film scans to create a tangible archive of their work.

“I'm starting to consider myself an amateur historian,” Chloe said before taking a sip of their iced matcha — quite an understatement. It’s clear from their work and our discussion that history is at the center of their desire to cover and create work tackling serious social issues. In our conversation for CHUM News, Chloe went on to trace the history of Seattle, explain the work that turned into “Boiling Point”, and celebrate their relationship with the young people they teach through Youth in Focus, a local photography non-profit, as well as other educational programs.

The following conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Chloe Collyer: As queer and Black, I really am interested [in Seattle history]. I love to know my history and know more about West Coast Black queer stuff. I recently pulled out my tome of a book on the [Central District, The Forging of a Black Community]. It stops in ’69, so it's like the first half of the 20th century. And I just scrubbed the whole book for the word queer or anything, especially because, like, the CD used to extend to Capitol Hill. What happened? There must have been a time when Black people came up against some white queers. I want to know that story, and it’s nowhere to be found in this book. So I have some specific-ass research to do because it's like, when you think of Seattle, you think of grunge, gay, white.

Meron Menghistab: Yeah, I don’t know enough about that time.

CC: I really love history. I'm starting to consider myself an amateur historian.

MM: I look at your approach to documentation as historical, and I look at you as a historical operative.

CC: Anytime I'm going out to cover something, I'm reading the history of that topic in Seattle. I'm going into the state archives, and trying to learn what's different and what's the same about the patterns that happen here. And my family's been here for so long: I'm trying to take things from my oral history of my family, and from Indigenous history, of course. That's what this new project is trying to do a little bit, even though it’s pulling from my archive of digital stuff. I really would like to do more projects that feature archival photographs, Black history, et cetera.

MM: I really enjoy photographers creating new things from their archives. That conversation with yourself is really important. Can you talk a bit about what made you go for a multimedia approach for this project? You’re actively a photojournalist, so it’s really cool to see your pivot to thinking about the archive.

CC: This piece I read talked about life as an archive in addition to other non-physical bodies of work, including oral history. And so it expanded my mind to think about what an archive is. I have a [Finding Nemo’s] Dory-ass memory: I have to look through my pictures constantly. I enjoy looking through to remember who's there. Maybe I've met someone recently, and Oh! they're in a picture from four years ago. I mean, it's impossible to remember all the things I've covered.

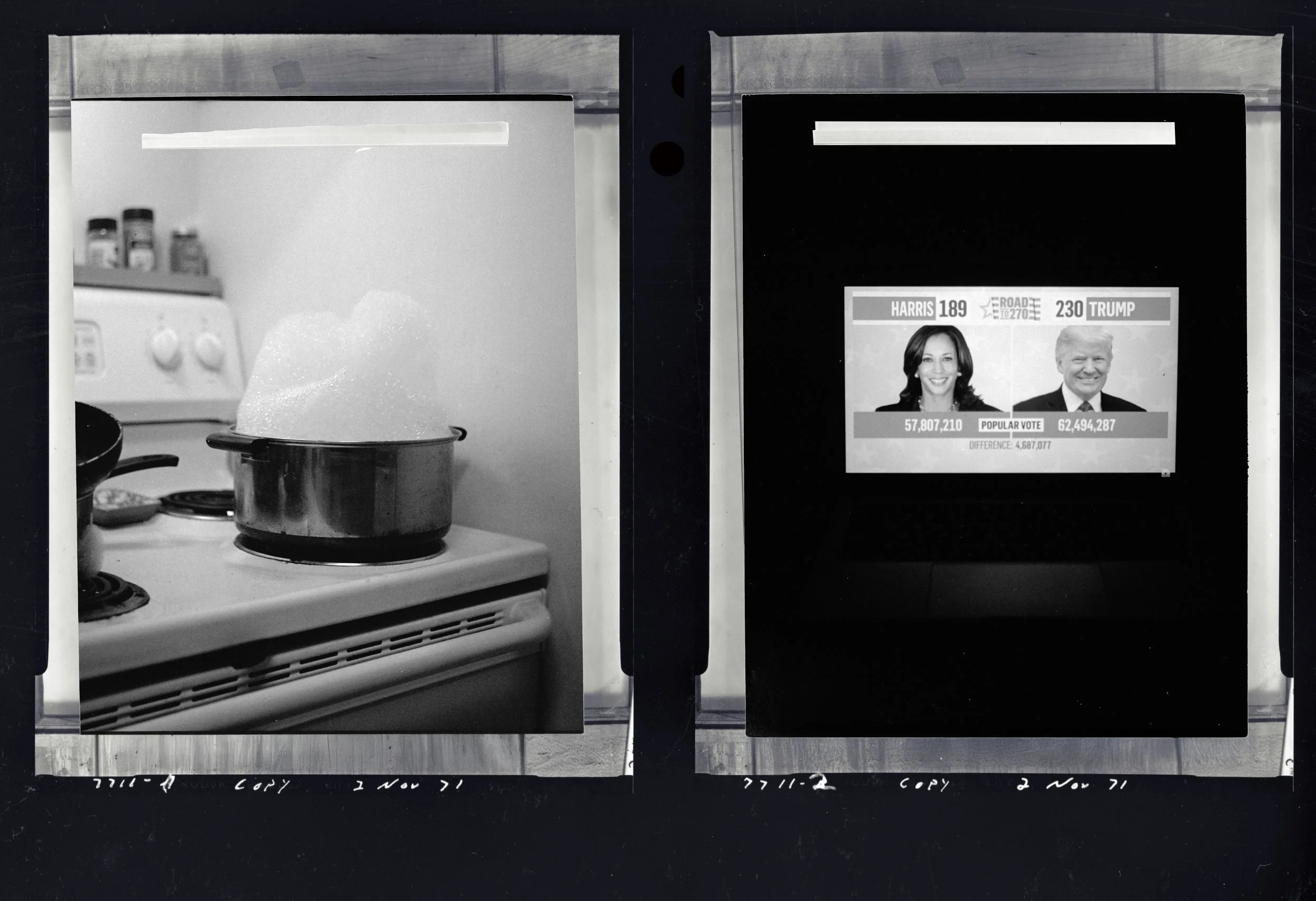

BOILING POINT DIPTYCH: CHLOE COLLYER, 2025

“My love for film feels so connected to my love of archives and history”

Also, just being reflective about this period in our country and in politics, and looking at the kind of breadcrumb trail I’ve left for myself, I really, really wanted [the project] to be physical media. So I just allowed myself to regenerate my photos.

Since becoming a photojournalist, I haven't identified as an artist at all. Growing up, I always felt like an artist. I was doing multimedia, poetry, photography, I was a musician, but photojournalism doesn't feel like art to me. And a lot of people say that I'm incorrect in that, but that's just how I feel. It doesn't feel like art to document reality in the most real way, in literal terms. Of course, composition is an art. Point of view is an art. But it feels like a literal interpretation, and so visually, I wanted this project to look like art, like the way I want it to.

I personally would not want to hang any of my photojournalism photos on the wall as fine art. And I think part of that is trauma — that it doesn't feel like a good memory, even the happy stuff, even the happy moments — so I was able to distance myself from the work by putting this layer of like a film effect on it. And my love for film feels so connected to my love of archives and history, and I wanted my photos to feel more like a piece of history by affixing it to film. It felt like combining those two was just right.

I also gotta flex real quick, because my work is hanging in the Library of Congress.

[Meron leans in closer to the recorder.]

MM: Say that again!

CC: I have yet to go see it! But that was mad validating, to have them call me and be like, your work is history on a national level, and is worth archiving.

MM: I do think a big reason millennials, Gen Z, whatever, anyone who's making photographs right now, when we talk about, like, Why is everyone shooting film again? I do think a big part of it is the emotional rejection of how fast things move through social media. People want a negative. When I have a negative, it can't move. It won't get lost to an algorithm. It won't get buried in a feed. It's there and it stays wherever I put it. And I think whether people want to admit it or not, due to the nature of our industry, let alone photojournalism, there’s now so much digital work, and so to want to react to that by making an archival film project makes sense.

CC: Yeah. And now, I do worry about all my stuff being on a hard drive, in Google (Drive) — but like, trust, bro, I need triplicates of everything.

MM: Outside of your photography career, you are an educator working with a lot of kids who grew up like us, which is a powerful thing, and who grew up around the same things we grew up around. How do you see their relationship with photography forming?

Also, it's interesting: You have two different realms, in school, and outside of it, through after-school programs. When it comes to the surveillance aspect, do they feel comfortable photographing protests? They have such a different relationship with surveillance than we do. Whether it's right or wrong is irrelevant; they have a different relationship with it.

CC: They love cameras. I mean, to every kid, every young person, it's a tool. It feels like a toy. Sometimes I think whether you want to be a photographer or not, like, buttons are fun to push! Whether you're someone who's like, Yeah, I'm looking cute today! I'm gonna do selfies with my friends, or just, like, purely documenting nature.

I work with ages 10 to 18, and by that age, they are passionate about something, so I just tell them: Whatever is your thing, please use a camera to document that, because you're the expert, and that is what makes good journalism great. It's because you become an expert in what you are covering, whether it's lived experience or research or a combo. Youth voices are already underrepresented in art and in storytelling, and y'all know that, so already what you're doing is radical; just by clicking and showing someone [your work], you're amplifying your own voice. And they definitely tap into that.

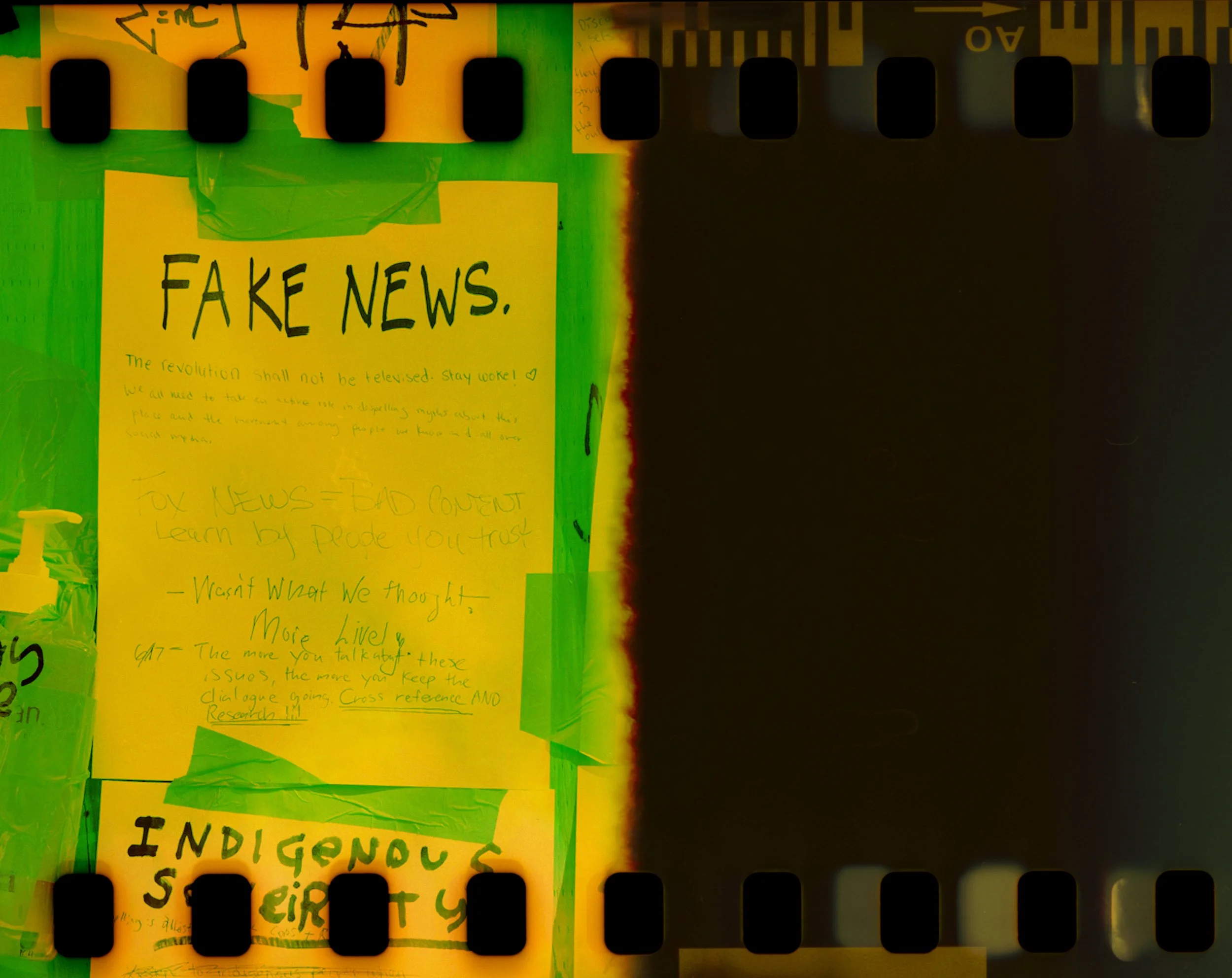

One thing that's interesting, and that's different from my generation, is that on day one in every single class, we talk about consent. Consent was not in the dictionary when I was a teenager, let alone whether it's physical, emotional, artistic. And so to have a classroom of kids of all different background types understand consent, be able to define it, and be enthusiastic about it, is great.

Then we get into your legal rights as a photographer in public. And I always ask them, Do you think you're allowed to take pictures of what and whoever you want? When you're on the street, when you're at a protest, can you just photograph whoever you want? Usually they're not sure, or 50/50, but a lot of kids emphatically say, No, there's no way you can just photograph whoever. And they're surprised by the truth. There's always a group that's like, Oh, I can just be captured or photographed like that in public? That is a common wake up call for all kinds of people, because we all need media training. You are a citizen of the internet.

SHARIA SPLIT: CHLOE COLLYER, 2025

SHARIA SPLIT: CHLOE COLLYER, 2025

“As far as the documentation [goes], that will always keep going. I cannot stop: I do it because I would be there anyway.”

I think a lot of students default to being really consensual and ethical with their photography, especially when it comes to taking pictures of people. That's the main difference. No matter their age, the first step of being intentional with your photos is so powerful, and that's all I'm hoping for: for them to either pre-visualize something and be like, Oh, this is what I want, or at least be proud enough to show someone else. It's like, you need to stand on business and show the work. One of the only required parts of my class is that you make something you're proud of enough to put on the wall. Because if you're an artist that can't do that part, you're not going to be — I don't even want to say successful — you're not going to be fulfilled.

MM: Speaking of putting art on walls, with “Boiling Point,” it’s in conversation with your archive, but it’s based on work you will, I assume, continue making. Does it feel like you're done with it, like you just need to get it out? Or is it something that you feel like you're gonna keep growing? There's probably not a direct answer to that necessarily, but it’s been a really polarized past 5 years in politics. [CHUM NEWS knows that’s a comically reductive statement.]

CC: Yeah, I think that's why it's called “Boiling Point.” I would like to think of this time, at least in my communities, as a peak point that we have to come down from. It can't get any worse. It can't get any more tense. I definitely think it's timely in the sense that it's also been therapeutic for me. As someone creating the work and getting a lot of therapy, I actually teared up making some of it, because I get disconnected from the work, and then to look at it again and really reflect on what's happening in the world, and see these images — it's really a lot of emotion to put down.

So for that reason, and many reasons, it will have a cap on it. But as far as the documentation [goes], that will always keep going. I cannot stop: I do it because I would be there anyway. And so that's my love language: it’s to give my gift to people, documenting. So that's what it's really about. But yes, I want this project to have an end point.

MLK GAZA PROTEST: CHLOE COLLYER, 2025

See more of Chloe Collyer’s work on their website